Sunday 15 November 2015

Bitter irony

The last time I posted here. it was a look at the Doctor Who story The Massacre. Bloodshed in the name of religion on the streets of Paris. I could cry at the irony. Plus ca change, plus c'est la meme chose.

Monday 19 October 2015

History With The TARDIS - The Massacre

The Massacre of St Bartholomew's Eve (1966).

Time for another look at an historical event as seen through the lens of the time-traveling Doctor.

On screen, the Doctor and his companion Steven Taylor arrive in Paris in the late summer of 1572. The Doctor decides to go and seek out the apothecary Charles Preslin. Steven is left in a tavern, where he meets a group of young Huguenots.

The city is full of visitors who have come to celebrate the wedding of Marie de Medici, of the Catholic Royal Family, to Henri of Navarre, a Protestant. The Queen Mother, Catherine de Medici, hopes that the union will help to soothe the religious turmoils besetting the country. France is a predominantly Catholic realm, and Protestants are tolerated at best, but persecuted in many regions.

Steven gets involved with a conspiracy which is being planned by the Abbot of Amboise - who just happens to look exactly like the Doctor. A servant named Anne, who works for the Abbot, has learned of a planned massacre. Steven has to protect her from the Catholic forces, but makes an enemy of his Huguenot friends when he identifies the Abbot as his acquaintance.

The Abbot is behind a plot to assassinate Admiral de Coligny - the leading Protestant minister who is liked by young King Charles IX. When this plot fails - the Admiral only being wounded - the Abbot is killed, and Steven thinks it is the Doctor who has died.

Fearing that the Protestants will rebel against them, Catherine de Medici decides on a preemptive attack on them.

Steven eventually manages to find the Doctor alive and well at Preslin's shop. On learning the date - 23rd August - the Doctor realises they are in grave danger and they depart - just as the massacre of the Huguenots begins...

The story is credited to writer John Lucarotti, but much of it belongs to script editor Donald Tosh. Of all the periods of Earth's history visited by the Doctor, this is one of the most obscure. Many people know of the broad strokes of the Reformation / Counter-Reformation, but specific events in individual European countries have never made it to British school syllabuses - except for Henry VIII. Viewers in 1966 would mostly be finding out about the events of St Bartholomew's Day, 1572, for the first time.

One thing to mention straight off is the title of this story. It is generally shortened to The Massacre. The full title is wrong - as the massacre took place on the feast day itself - not it's eve.

As the story covers the build-up to the massacre, the word "Eve" should really be put to the beginning of the title.

Tosh has done his homework, as events which form the background to the story are fairly accurate. The Doctor look-alike Abbot of Amboise is entirely fictional.

The Catholic Queen Mother really did want the marriage of her daughter to Henri of Navarre - the future King Henri IV of France - to soothe tensions, but she wasn't hopeful of its success. She was unhappy at the influence Gaspar de Coligny had over the young King Charles IX. de Coligny was hoping to dissuade France from taking action against the Protestant Dutch, and this went against the policies of the Catholic ministers.

The Admiral was shot in the street on his way home from a cabinet meeting, and was badly wounded. The city was full of Huguenot supporters of Henri, and they were naturally incensed at the attack on their leader. Fearing Catholics would be massacred, the decision was taken to kill every Protestant who could be found in the city.

The signal for the massacre to begin was the tolling of the bells of the church of St Germain-l'Auxerrois, close to the palace of the Louvre. The medieval tower can still be seen today. de Coligny was dragged from his sick bed, killed, and his body dumped from an upper window. King Charles is said to have shot Huguenots for sport from the palace windows.

The killing went on throughout the 24th of August. Massacres then spread out from Paris to take in all of France over the next couple of weeks. The exact death tolls are not known, but it has been estimated that about 2000 died in Paris, with a further 3000 in the provinces.

In the longer term, all of Catherine de Medici's sons became king - but all were short-lived. Charles died 2 years after the Massacre. His brother Henri III was assassinated. As mentioned above, Henri of Navarre eventually became king, though he had to convert to Catholicism to do so. He is said to have claimed that "Paris is well worth a mass". He introduced religious tolerance policies, such as the Edict of Nantes, allowing Protestants to practice their faith unmolested. Ultimately, he was also assassinated - by a Catholic fanatic.

It was the events of 24th August 1572 that introduced the word "massacre" to common parlance. One consequence for England, was the influx of Huguenot refugees to the City of London. You can see their houses if you take a walk around the Spitalfields area - as my next post will show.

Sadly, you can't enjoy this Doctor Who story any more - it no longer exists in the archives except for its soundtrack.

Saturday 26 September 2015

Update - and Apologies

Apologies, but with a new job - and a new series of Doctor Who transmitting - this blog has been neglected of late. I am actually going on a walk round Fitzrovia / Bloomsbury tomorrow, and also have a Who / History crossover post ready to go.

There will also be another of my looks at the history of the London Underground lines.

Normal service will be resumed in the next couple of days.

There will also be another of my looks at the history of the London Underground lines.

Normal service will be resumed in the next couple of days.

Friday 28 August 2015

Sherlock's Final Resting Place

Back in January I attended a wedding in the New Forest, Hampshire. The day after the festivities, a few hardy souls decided to clear their heads by taking part in a car treasure hunt around the area. One of the locations we visited was the tiny village of Minstead - and I was surprised to come across the grave of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Surprised, as I knew he was born in Edinburgh (in 1859), lived for many years in South Norwood (not far from where I currently live) and died in Crowborough, East Sussex (in 1930).

It transpires that this was not his first burial place. He was reburied alongside his wife in Minstead later.

The church is called All Saints. It dates, in part, from the 13th Century. One of the pews, reserved for the local gentry, even has its own fireplace, unusually.

There had been some controversy regarding Doyle's burial, as he maintained that he was not a Christian. He regarded himself as a Spiritualist.

Wednesday 19 August 2015

Gordon Square and the Bloomsbury Group

Inspired by the BBC's recent drama "Life In Squares", about the Bloomsbury Group, I thought I would have a wander round the area that gave them their name. (Ignore the date stamp on the pics - I haven't a clue how to change it. I usually use my phone but it has recently had a falling out with the laptop and refuses to import pictures :-(

The Group was formed at Cambridge University as the 19th Century gave way to the 20th. Unlike other artistic groups of the same period, they did not have any political agenda, or issue any kind of manifesto. It was simply a group of writers / artists who shared a particular philosophy towards their work and the way they lived their lives.

The core members were the Stephen sisters (painter Vanessa and writer Virginia), Clive Bell, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, E M Foster, Roger Fry, Gwen Darwin (granddaughter of Charles) and the economist John Maynard Keynes. Vanessa is better known by her married name (she wed Clive Bell), and Virginia by her married name - Woolf.

As well as the body of work they produced, the Group is well known for its interpersonal relationships. Duncan Grant, for instance, had sexual relationships with his cousin Lytton Strachey, and Keynes, and Vanessa Bell.

|

| Victoria House, Bloomsbury Square |

Bloomsbury Square, part of the Bedford Estate, which gave the area its name, is fairly non-descript these days. The southern side is a busy main road. It is dominated by the huge Beaux Arts Victoria House on the east side. This was considered for the seat of the Mayor and the London Assembly for a time, until it was decided to create a new building on the south side of the Thames opposite the Tower of London.

(It is said that the reason the nearby Senate House of UCL was spared bombing during WW2 because Hitler had his eye on it for his HQ were an invasion to be successful).

|

| 46 - 50 Gordon Square |

No.37 was home to Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant in 1925.

No.46 was an earlier home for Vanessa (from 1904). John Maynard Keynes moved into it a few years later.

No.50 was Clive Bell's address between 1922 - 39, and where the Group regularly met.

No.51 was home to Lytton Strachey from 1919.

There are a number of other addresses in the vicinity which were closely associated with the Group, but which no longer exist - thanks mainly to WW2 bombing:

38 Brunswick Square was home to 5 members of the Group between 1911 - 12.

34 Mecklenburg Square was where Virginia Woolf volunteered for a Suffrage group just before the First World War. It later became HQ for the Women's Trade Union League.

She and her husband, Leonard, moved into No.37 in August 1939.

Before that, she lived for 15 years at 57 Tavistock Square. It is now the Tavistock Hotel.

At the south west corner of Gordon Square is Byng Place. Here stands the University Church of Christ the King. Built between 1851 - 54 for the Catholic Apostolic Sect, it was supposed to have the tallest spire in London, but this never materialised. The sect died out and in 1963 it was leased to the Church of England for use as the UCL chaplaincy. The church has a collection of ceremonial vestments - including one that is reserved exclusively for Christ, should he ever make his Second Coming.

Whilst the output of the Bloomsbury Group is globally admired, the members were disliked by those outside their circle.

Rupert Brooke, the poet, described the "rotten atmosphere in the Stracheys' treacherous and wicked circle". D H Lawrence hated "this horror of little swarming selves". Wyndham Lewis referred to them as "elitist, corrupt and talentless".

A recent BBC series on Bohemianism tackled the Bloomsbury Group and found against them - as they were all from privileged backgrounds and so could afford to live the way they did. Spolied snobs, basically. Real Bohemians don't just play at being so. The same programme was pretty negative about the whole current Hipster style. Unimaginative clones, basically.

I do admire the Group's work. And Keynes should not be blamed for that New Town just north of London that bears his name.

Saturday 15 August 2015

Update

Have been rather busy with the Doctor Who blog, plus other stuff. Expect an update in the next couple of days. Just watched the BBC's Life In Squares, and have been inspired for a trip into Bloomsbury...

Friday 31 July 2015

Lunch with Blake, Bunyan & Defoe

This afternoon I found myself sitting on a bench eating lunch next to the poet John Bunyan. That's the writer of Pilgrim's Progress. Who died in 1688.

I was in Bunhill Fields - a cemetery on the northern edge of the City. It lies in the Finsbury district, between the Northern Line stations of Moorgate and Old Street.

The name is a corruption of "Bone Hill". In 1549 a massive number of bones were moved here from the churchyard of St Paul's Cathedral. Later, from 1657, it became the leading Noncomformist Cemetery. Following the Civil Wars of the 1640's, a number of Protestant sects established themselves. Only Anglicanism was recognised by the state, and followers of these other movements found they could not be buried in Church of England graveyards.

It remained London's principle dissenters' cemetery until 1854, when the laws relating to religion were relaxed. (The Burial Act of 1852 had also come into force). There are an estimated 230,000 inhumations in the Fields, and some 2000 graves are still marked today.

Daniel Defoe (of Robinson Crusoe fame) wrote an account of the Great Plague of 1665 - A Journal of the Plague Year - and he states that Bunhill Fields was used as a plague pit. He claims some stricken individuals, mad with fever, threw themselves into the pits and expired. Defoe himself was later buried here. He was on the run from creditors when he died, so was buried under the name Mr Dubow. The obelisk marking his grave was stolen, and turned up down in Southampton. After a time in Stoke Newington Library, it was returned to Bunhill Fields where it can be seen today. Just next to it is the tombstone of the visionary painter and poet William Blake, along with his wife.

As you can see from the image above, the stone does not mark the actual location of his body.

Just across from the City Road entrance to the Fields is the Chapel and House of the Methodist leader John Wesley. His mother, Susanna, is buried in the Fields. Also here is the poet Robert Southey.

Quakers had there own separate section of the cemetery. George Fox, one of the founders of the Quaker Movement, is buried there.

Some more views of the Fields:

Above is the tomb of Dame Mary Page (d. 1728). She was the wife of shipping magnate Sir Gregory Page. On the opposite side to this inscription is another which states that over 67 months some 240 gallons of water were extracted ("tapp'd") from her. This obviously refers to some medical complaint from which she suffered - and presumably died from - involving retention of water in the body.

Today it is a popular place for City workers to enjoy an alfresco lunch in the finer weather.

Part of the grounds are used by the Honourable Artillery Company, which is based next to the Fields. The HAC is the oldest military company in London - Finsbury Fields used to be used for archery practice from the Tudor period. These grounds saw some of England's first ever cricket matches.

I have had a good long look and cannot find any good ghost stories attached to this cemetery. Quakers and Methodists obviously rest easier in their graves...

Saturday 25 July 2015

St Anne's Limehouse

Like St George-in-the-East, a church by the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor - assistant to Sir Christopher Wren. It was another of the churches built as part of the "50 New Churches Act" during the reign of Queen Anne. The parish of Limehouse grew out of the old parish of St Dunstan's, Stepney, in 1709. The building was completed in 1727, and consecrated in 1730.

The clock is the highest church clock in London - as it had to be seen by shipping on the Thames. The gold ball at the top of the tower was used as a navigation marker for shipping. The church has had a long association with the navy. When the last HMS Ark Royal was decommissioned, the Ensign flag was presented to St Anne's.

The church was gutted by a fire in 1850, but managed to survive the Blitz. Beneath the Portland Stone flooring is the original Queen Anne brick surface.

The church features prominently in the works of author Peter Ackroyd - in Hawksmoor and Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem.

Nicholas Hawksmoor has gained a reputation for having been more interested in paganism than Christianity. This is partly due to a pyramid that sits in the graveyard of St Anne's. This has "The Wisdom of Solomon" carved upon it.

Many believe this mysterious structure demonstrates Hawksmoor's interest in ancient masonic rites and sacred geometry. However, the pyramid was simply supposed to cap one of the corners of the church but Hawksmoor changed his mind and set it up in the yard. This fact hasn't stopped the conspiracy theorists. The pyramid has its own separate Grade II listing.

The war memorial, with a statue of Christ in bronze and a plaque featuring a WWI battlefield also has its own Grade II listing.

Monday 13 July 2015

History With The TARDIS - The Visitation

A Doctor Who story with a conclusion set in London, 1666? It can only mean the Great Fire.

The bulk of this story sees the Fifth Doctor, with companions Tegan, Nyssa and Adric, encountering the survivors from a crashed alien escape ship. These reptilian Terileptils do not want to be rescued, however, as they are escaped convicts. They would rather take over the Earth as their new home - getting rid of the human inhabitants using a genetically engineered variant of the plague. This takes place in 17th Century Middlesex - round about where Heathrow Airport will be built in a few centuries time.

The Doctor must track the Terileptils to their secondary base which has been set up in London. The plague-infected rats are being stored in a bakery here awaiting release. In a struggle, a burning brazier is knocked over and one of the alien handguns falls into the flames. The aliens use a highly flammable gas to compensate for Earth's atmosphere - and when the gun explodes it starts a major conflagration. The Doctor works out what this means for history - saying this fire should be allowed to run its course. When the TARDIS dematerialises, we see the name of the street where the bakery is situated - Pudding Lane...

One of those occasions when the Doctor is responsible for a major historical event - one that he is unable to alter.

The real Great Fire did indeed begin in a bakery - that of a Thomas Farriner (or Farynor) - in Pudding Lane. It started in the chimney of the shop just after midnight on September 2nd. Apart from the big civic buildings, this was a city of wood, with houses crammed together on narrow streets. The fire quickly spread to adjoining properties.

There wasn't any fire brigade in these times, just the watchmen who patrolled the streets plus local militia known as the Trained Bands. Each parish church had to hold equipment for fire-fighting - ladders and long fire-hooks. The latter were to help pull down building that were already ablaze or at risk of fire. This would create fire-breaks, that a fire would not be able to cross.

When the Lord Mayor of London - Sir Thomas Bloodworth - was informed of the fire, he is supposed to have exclaimed: "Pish! A woman could piss it out." Diarist Samuel Pepys was woken by a maid at about 3am. He took a look, considered it not much of a threat, and then went back to bed. By morning, the full extent of that threat was becoming apparent.

The Mayor's failure to take the fire seriously and create fire-breaks in the first few hours had meant that it had spread over a wide area of the City. The previous month had been extremely dry, and there was now a strong easterly wind. Once the fire reached the river side, it met with a number of highly flammable materials being stored in the numerous wharves and warehouses. Pepys went to the Tower to observe the fire from on high, then set off by boat to Whitehall Palace to report to King Charles (II) and his brother the Duke of York. Later, Pepys settled himself at an inn on Bankside, in Southwark, to watch the progress of the fire from there. When his own home was threatened, he buried his most prized possessions in the garden - including his cheese.

People whose homes had burned were forced to move further and further away - some having to transport their belongings four or five times in a day, as the fire continued to spread wider and wider. The various city gates became congested with people fleeing the city. Finsbury Fields would eventually become a tented town for those made homeless.

The fire did not abate until September 5th.

It had destroyed more than 13,000 houses, 87 churches, 44 Company Halls, and three City Gates, as well as major buildings such as the Royal Exchange and the Guildhall. Its most famous casualty would be the medieval St Paul's Cathedral. The lead from its roof melted and ran down the streets.

The official death toll was only 6, but this is widely believed to be a gross underestimate. There would have been many people living in the affected areas who were not properly registered with the authorities. The heat from the fire would have totally cremated bodies - leaving little sign.

One thing the Doctor might have found ironic is that aliens were blamed for starting the fire. These aliens were foreigners - especially Catholic ones. One Frenchman did actually admit to starting the fire deliberately, and he was hung for it. However, it was then discovered that he did not arrive in the City until after the fire had been raging for two days. He was at sea when it began.

Some lynchings and other attacks were reported on foreign tradesmen, though many thought these merely used the fire as an excuse to get rid of business competitors.

Plans to totally redesign the layout of the city came to nothing, due to the complexity of the land ownership. This means that the narrow winding street named Pudding Lane can still be visited today.

"Pudding" does not refer to delicacies cooked up by Thomas Farriner's bakery. "Puddings" were piles of stinking offal from slaughtered animals which dropped to the ground as they were transported down this street to be dumped in the Thames.

There are two monuments to the Fire to be seen in London today. One is the golden cherub statue at Pye Corner, Smithfield (subject of an earlier post), and of course The Monument.

Until 1830, the plaque at the base of the Monument continued to explicitly blame Catholics for causing the fire. The height of the Monument is the same as the distance from its base to where Farriner's bakery stood. At the top is a golden urn with flames. Sir Christopher Wren wanted to place a statue of King Charles on top, but he refused, saying "It wasn't me who started the fire...".

Wednesday 8 July 2015

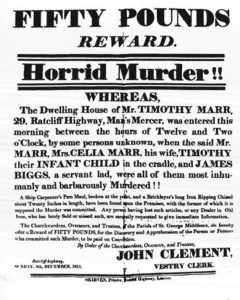

St George-in-the-East and the Ratcliff Highway Murders

St George-in-the-East is a Hawksmoor designed church, built as part of the Fifty New Churches Act during the reign of Queen Anne. It was constructed between 1714 - 1729. It lies south of Whitechapel, and north of Wapping, at a junction between Cannon Street Road and the Highway.

In 1850 it was the scene of a dispute between High and Low Church Anglicans. (High Church services have more ceremony - something Low Church followers feel is too close to Catholic rites). When the Bishop of London appointed a Low Church man to the parish, the locals demonstrated their disapproval by keeping their hats on, smoking their pipes and encouraging their dogs to bark in the church.

The church interior was destroyed when a bomb hit it in May 1941. Only the shell of Hawksmoor's building survives. Within is a smaller, modern church, built in 1964. There is a Montessori School in the crypt.

The gardens - St George's Park - to the east are built on the church's graveyard, so the walls have old gravestones along them. A number of tombs and monuments are still scattered about the lawns.

In one corner of the park there is also the burned out shell of what was once a small natural history museum.

The entrance to the park from the north - Cable Street - takes you past the famous mural depicting the 1936 "Battle of Cable Street", when the local Jewish population and a number of socialist groups joined forces and prevented a march by Oswald Mosley's Fascist Blackshirts from marching through the area.

In the grounds of the church are buried victims of East London's most notorious murders, after the Ripper killings. The street which now runs east towards Limehouse called the Highway was once known as Ratcliff Highway (Ratcliff being a corruption of red cliff - a topographical feature of the area).

A search of the house found nothing missing, and a large quantity of money still intact, so it was assumed that the killers had panicked and fled when Margaret returned. Footprints found at the back of the house seemed to show that there had been more than one person involved.

On December 19th, a second set of killings took place nearby. The publican of the Kings Arms on New Gravel Lane - John Williamson - was murdered in equally barbaric fashion, along with his wife and servant girl. The alarm was raised when a lodger - John Turner - lowered himself from an upper window, half dressed and screaming "Murder!". This time there was survivor - Williamson's 14 year old grand-daughter, but she had not seen the killer(s).

On December 24th, the landlord of the nearby Pear Tree Inn identified the murder weapon - a sailor's maul - as belonging to one of his lodgers. This man had been at sea at the time of the killings, but his fellow lodger, John Williams, knew the Marrs and had often drank in the Kings Arms. He became the prime suspect and was imprisoned in Coldbath Fields Prison, Clerkenwell.

Here, on 28th December, Williams hanged himself with his scarf. The suicide was taken as a sign of his guilt. No other comparable killings took place after he died.

The police were happy to presume that he was responsible for both sets of killings. The motive for the killings has never been identified. Despite there being physical evidence, and some witness statements, to support there being more than one killer no-one else was ever charged.

Williams was buried on January 1st. His body was wheeled through the area, stopping for 15 minutes outside the Kings Arms. He could not be buried in hallowed ground as he was a suicide, so he was interred beneath the crossroads outside the church of St George-in-the-East. A stake was driven through his heart. The stake was to stop the soul wandering, whilst the position at a crossroads was designed to confuse any restless spirit.

The body was dug up in the late 1800's when gas mains were being laid. The skull was kept by the landlord of the nearby Crown & Dolphin. It was displayed for many years, but its whereabouts are now unknown.

Friday 3 July 2015

Going Underground No.2

The District Line.

After the success of the initial 7 stations on what is now known as the Metropolitan Line, ideas poured in for other underground railways. One person suggested a circular line around the city - encased in glass. Another person suggested draining the Regents Canal and laying tracks on its bed.

The idea that proved most popular was a line that ran along the Thames.

Green on the map, it is one of the shallowest tube lines - and was recently voted the second worst line to travel on (You Gov poll).

Originally named the Metropolitan District Line, work began in June 1865.

The first stretch - between South Kensington and Westminster opened in time for Christmas 1868. It was then extended eastwards to Blackfriars - making use of the Victoria Embankment.

Following what became known as "The Great Stink" - when pollution of the Thames got so bad in the summer of 1858 that the City ground to a halt and MP's in Parliament could only work by saturating their blinds with chloride and lime - a new sewer was planned to take all of the effluent that was currently emptying into the river and channel it out to the east of the city - downriver.

Joseph Bazalgette's great sewer was built by embanking the river front. Today, the buildings on The Strand are backed with wide pavements and roads, when once they backed directly onto the Thames.

Where the people working in the image above are, there was once river and foreshore.

The reclaimed area was big enough to take the sewer - and the new underground line.

Further extensions to the District Line were to Hammersmith (1874), Richmond (1877), Ealing Broadway (1879), Putney Bridge (1880) and Wimbledon (1889). Extensions to Uxbridge and Hounslow were transferred to the Piccadilly Line in the 1930's.

We'll start out journey in the west where these extensions cover.

Richmond: An overground railway station has been here since 1846. One of the early plans for Crossrail would have seen it come here - in place of the District Line.

Kew Gardens: Opened 1877. It is the only tube station still to have a pub attached to it, though the connecting door to Platform 1 has now been blocked off. In the 1940's, the nuclear scientist Klaus Fuchs used to meet his KGB contact at the station. The building lies in the Kew Gardens Conservation Area, and so remains an original 19th Century structure.

Gunnersbury: The overground station opened as Brentford Road in 1869. On 8th December 1954, a tornado ripped the roof off the station, injuring six people.

Ealing Broadway: A GWR station was built here in 1838, but the underground station was built some distance away.

Ealing Common: Opened as Ealing Common then changed to Ealing Common and West Acton, before reverting back to the original name. The station building was replaced by a Charles Holden design in 1931.

Acton Town: Opened as Mill Hill Park, changing to Acton Town in 1910. It is nearly a mile away from the centre of Acton. Nearby are the Acton Works - once the Underground's main repair facility and now where the Transport Museum keeps its reserve stock of road and rail vehicles (open some weekends through the year).

Chiswick Park: Opened 1879 as Acton Green. Charles Holden rebuilt the station in the early 1930's in anticipation of the Piccadilly Line sharing it - something which never transpired. This station is closer to Turnham Green than Turnham Green station is.

Turnham Green: Source of many puns. Built on the site of a failed assassination attempt against King William III. A plan to have the Central Line also use this station was abandoned due the onset of the First World War. Once the war ended, a new route was proposed instead. In 1878 a passenger was injured due to the fact that the height from the platform to the carriages was 2 feet. None of your step-free-access in Victorian times. (Even today, at Bank Station, there is a 1 foot horizontal gap between the platform edge and the carriages).

Stamford Brook: Named after one of London's lost rivers (now channeled underground, it rises at Wormwood Scrubs and enters the Thames at Hammersmith, separating Upper and Lower Mall. The first Underground station to have an automatic ticket barrier (they've been trapping our belongings since 1964).

Ravenscourt Park: Opened as Shaftesbury Road in 1877. The first station to have its platforms raised after that accident at Turnham Green mentioned above.

Hammersmith: The Metropolitan Line and the District Line had separate station across the road from each other. They were only linked, from a pedestrian point of view, relatively recently. Scene of a derailment in 2003 caused by a broken rail. The subsequent inquiry found that the rails across the entire network were not being checked as frequently or as thoroughly as they should.

Barons Court: The name has nothing to do with nearby Earl's Court. It comes from Barenscourt in Ireland. The developer of this area, William Palliser, had connections there. (Many of the local streets are named after family members). This is why the name has no apostrophe, unlike Earl's Court.

West Kensington: Opened in 1874 as Fulham - North End. In 2009, after spending over £5m on refurbishment, plans to make the station step free were abandoned.

Kensington (Olympia): On a little extension on its own, between 1946 - 86 only open when exhibitions were running. It reverted to this state in 2011.

Wimbledon: Opened in 1889. Confuses tennis fans as it isn't the closest station to where the Championships take place. Between 1949 and 1956 the mainline station was base of operations for an Airedale Terrier named Laddie. With a box strapped to his back he collected money for railway charities. When he died in 1960, he was stuffed and displayed on Platform 5 of the station, but since 1990 has been housed in a museum. There is now an interchange with the Tramlink service - which confuses the heck out of Oyster users. You can't touch out - you have to touch in a second time.

Wimbledon Park: The place for Andy Murray fans to alight as it is the closest station as the crow flies. However, the next station - Southfields - entails a shorter walk. Made the news in 2012 when the Surrey cricketer Tom Maynard was killed after being hit by a train when he was fleeing the police. He had been seen to be driving erratically nearby and ran off when stopped.

Southfields: As mentioned, the closest station to where the tennis gods summon rain - and Cliff Richard - every year. Underwent a major refurbishment in time for the 2012 Olympics as the tennis was being held here. Each year, the decoration of the platforms changes, depending on who the Championships' sponsors are.

East Putney: Opened 1889. The last overground train service ended here in 1941, but British Rail continued to own the station until 1994, when it sold it to London Underground for £1.00. Allegedly built on the site of a 17th Century plague pit.

Putney Bridge: Originally Putney Bridge & Fulham. The station is actually in Fulham, on the other side of the river from Putney. Fulham FC's Craven Cottage ground is about 1km away.

Parsons Green: The parsonage it was named after was demolished about two years after the station opened.

Fulham Broadway: Opened as Walham Green in 1880. It was renamed in 1952 after requests from Fulham's Chamber of Commerce. Nearest station to Chelsea FC's Stamford Bridge ground. Scene of a riot in May 2008 when Man United beat Chelsea in a Champions League Final. The only station to be name-checked in songs by both Take That and Ian Dury & The Blockheads.

West Brompton: Connected to the overground in 1999, though you have to go through the Underground to get to it.

Earl's Court: Originally just a small wooden station (burned down 1875), it is now a huge barn of a place (1915). Five different lines emerge from here. The exit to the exhibition halls is the smaller one to the west. Outside the larger east exit you can see a Police Call Box. (Just had to be mentioned...). The first escalators on the Underground were installed here in 1911. A one legged man named "Bumper" Harris was employed on the first day to go up and down them to prove they were safe.

High Street Kensington: Opened as Kensington (High Street). The station was built well back from the road in order to give direct access to the department stores Barkers, Pontings and Derry & Toms, who jointly owned the site. The stores ran special trains for their customers.

Notting Hill Gate: Named after a toll gate that used to stand nearby. Very busy every August Bank Holiday - Carnival time. A refurbishment in 1959 rediscovered lost lift passages, containing posters dating from 1900.

Bayswater: Originally Queen's Road. Then the street named Queen's Road was renamed Queensway, so the station became Bayswater. Two houses in Leinster Gardens had to be demolished during the construction of this part of the line. Fake frontages were put up to disguise this. (They appear in the 3rd series of Sherlock).

|

| The fake frontages of No's 23 & 24 |

|

| The view from the rear - with the tube lines running below |

Paddington: Opened as Paddington (Praed Street) to differentiate it from the Metropolitan Line station Paddington (Bishops Road). See also my post Going Underground No.1.

Edgware Road: Two stations of this name, serving different lines. There have been plans for years to rename one of them. Location for one of the bombs on 7th July 2005, killing 6 passengers.

Gloucester Road: It is a straight route east from here, now that all the various branches and extensions westwards have come together. Features in the Sherlock Holmes story The Bruce-Partington Plans - the one where the body gets dropped onto the roof of an underground carriage. Trains no longer stop at one of the platforms. It is used for art displays - Art On The Underground - viewable from the opposite platform. Surprisingly, the area around was still mostly fields and market gardens in 1869, as the OS map above shows.

South Kensington: The stop for the museums - V&A, Natural History and Science. The original western terminus of the line. Like its High Street namesake, the station is built into a shopping arcade.

Sloane Square: In the news just last week as London Underground have replaced the distinctive green wall tiles - with a white trellis motif, as this is the station closest to the site of the Chelsea Flower Show - with boring plain white tiles. The Sloane Rangers are not happy. In 1940 a bomb hit the station whilst two trains were on the platforms. The exact number of casualties was kept hushed up. The station was only reopened in 1951 as it was the closest to Battersea park, which was hosting part of the Festival of Britain. The River Westbourne passes above your head in a pipe above the platforms.

Victoria: One of the busiest and most overcrowded stations on the network. Passengers are locked out temporarily several times a day. They are currently building a new entrance, secondary ticket hall, and extra escalators - all to get you to the same number of platforms and the same number of trains. Pointless.

St James's Park: You need to come up onto the street to see its most distinctive feature. No 55 Broadway houses the HQ of London Underground, with a building designed by Charles Holden and decorated with statuary by Henry Moore and Jacob Epstein. At the time it was the tallest building in London. For many years the name did not include the apostrophe-s. New Scotland Yard is a short distance away on the other side of Broadway.

Westminster: The biggest engineering headache was making sure Westminster Abbey didn't fall into the hole when they were building it. Original eastern terminus of the line.

Embankment: Opened as Charing Cross, as it lies beneath the rail terminus of that name. Cross section above dates from 1914. Scene of an accident in 1938 when the signals were rewired wrongly. A Circle Line train collided with a District Line one. 6 people were killed, with 43 injured.

Warren's Blacking Factory used to stand on this site - where the young Charles Dickens had some of his formative experiences. The rest of his family were in debtors prison at the time.

Temple: Named after the nearby legal district. Had a lovely roof promenade over the station - closed within a year or so as it had became a favoured haunt of prostitutes. Originally The Temple - the definite article dropped out of use about the same time the prostitutes were banished.

|

| This illustrates how the embankment allowed the sewer and the tube line to be built side by side - the buildings on the left once being beside the water's edge. |

Mansion House: Bank Station is actually much closer to the Mansion House than this. At one stage it was planned that this would be the connection hub for all of London's underground lines.

Cannon Street: Built to link up the Circle Line. Used to be shut on Sundays and would close early in the evenings on other days as it served no local population - only commuters to the City.

Monument: Opened as Eastcheap. Another station built to link up the Circle Line. Connected by escalator to Bank Station. The two stations were jointly voted "least liked" in the same You Gov poll in 2013 that voted this whole line second least liked.

Tower Hill: Named specifically after the place where executions took place. Replaced an earlier station called Tower of London. There was another station just to the west called Mark Lane, which was closed as being too close to this. A substantial section of the Roman Wall can be seen just outside the station. This is the stop for the rail terminus of Fenchurch Street - the only London terminus not to have its own dedicated underground station.

Aldgate East: Longest platforms of any Underground station. The original station was some 500 feet to the west. The new station was built in 1938. A nearby station called St Mary's (Whitechapel) could then be closed. Danger of tripping over 'Jack the Ripper Walk' participants outside most evenings - one of their main meeting points.

Whitechapel: Once Whitechapel and Mile End. Jack the Ripper fans also congregate here. His first acknowledged victim was found north west of the station. John Merrick - the Elephant Man - was being exhibited in a freak show just a few yards away (just to the left of the image above). He died in a house only a few doors away from there. The Blind Beggar pub is a few yards off to the right. The East London line runs underneath - now part of London Overground. It will soon be connected to Crossrail as well.

Stepney Green: The actual Green is quite a distance to the south. Westbound passengers get told when their next train is due. Eastbound passengers only get told where the next train goes to - with no time stated. Some sort of anti-Cockney discrimination, surely?

Mile End: One of the few places you can change lines without leaving the platform. The name comes from a stone marking one mile from the eastern gate out of the City of London. This stone was actually much closer to Stepney Green. In 1918 a stampede during an air raid led to a number of fatalities.

Bow Road: The approach to the tunnel to the east of the station has one of the steepest gradients on the network - 1:28. Walford East, in the BBC soap Eastenders, is based on this station.

Bromley-by-Bow: Rebuilt in 1972 following a fire, it is one of the lesser used stations on the line - there not being much around it. An unexploded WW2 bomb was found by the tracks in 2008.

West Ham: In 1897, Arthur Hills, owner of the Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding Company, lobbied the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway Co. to build a station at Manor Road. This was so that people could easily get to visit the nearby Memorial Grounds where his works football team played. They were Thames Ironworks FC - who, in 1900, became West Ham United. The team play at another location now - so not the stop you want if going to one of their home games. Indeed, the plan is for them to move again - into the Olympic Stadium. In 1976, an IRA bomb detonated prematurely on a train at this station. 9 people were injured, but the train driver was shot dead when he tried to pursue the bomber.

Plaistow: A District Line station since 1902. Absolutely nothing interesting to say about it.

Upton Park: The station for West Ham United home games. Provides a quaint Cockney saying - to describe someone as "Upton Park" means they are a bit mad - being two stops short of Barking...

East Ham: As boring as Plaistow.

Barking: See Upton Park above. Terminus for the Hammersmith & City Line. The station was badly damaged in 1923 when a locomotive on the mainline collided with the buffers - leaving it hanging over the road below.

Upney: Officially the least used station on the line.

Becontree: Opened in 1932 to serve the Becontree Estate - at the time the biggest housing estate in the world. Reputedly haunted by a faceless woman in a white dress, with long blonde hair.

Dagenham Heathway: This was the nearest stop to Ford's Dagenham plant - famed for its globe-trotting Girl Pipers. See also the 2010 movie Made In Dagenham, which charts the women machinists' strike for equal pay. The theme song, written by Billy Bragg, is sung by Sandie Shaw - a local girl who once worked at Ford's.

Dagenham East: Scene of an accident in 1958 when a driver ran a red light due to dense fog. 10 people were killed and 89 injured. Legend has it that this incident is the source of the Becontree haunting.

Elm Park: Like Becontree, named after and built to serve a new housing estate in the 1930's. Unlike most other stations which had a separate ticket hall, here someone would sit in a little booth and sell tickets on one side, and collect tickets on the platform side.

Hornchurch: The station is a mile from the town of that name. The town gets its name from the 13th Century St Andrew's church, which is decorated with a horned bull on its gable end.

Upminster Bridge: Named after the bridge over the Ingrebourne river, which marks the ancient parish boundary between Hornchurch and Upminster.

Upminster: The most easterly station on the entire network, and the end of the line.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)